REVIEWS FROM THE COUCH

The Talos Principle II

The Talos Principle II

PUBLISHED

LAST UPDATE

24 October 2025

24 Ottobre 2025

GAME INFO

Title: The Talos Principle 2

Year: 2023

Release Date: 4 Novembre 2023

Developer Croteam

Publisher Devolver Digital

Genre: Puzzle

Tags: [coming soon]

ACCESSIBILITY

Input Keyboard, Controller

Lingua: Multilanguage

ITA: X

Trigger Warnings

TWs spoiler important parts or endings, thus are hidden.

Flashing lights

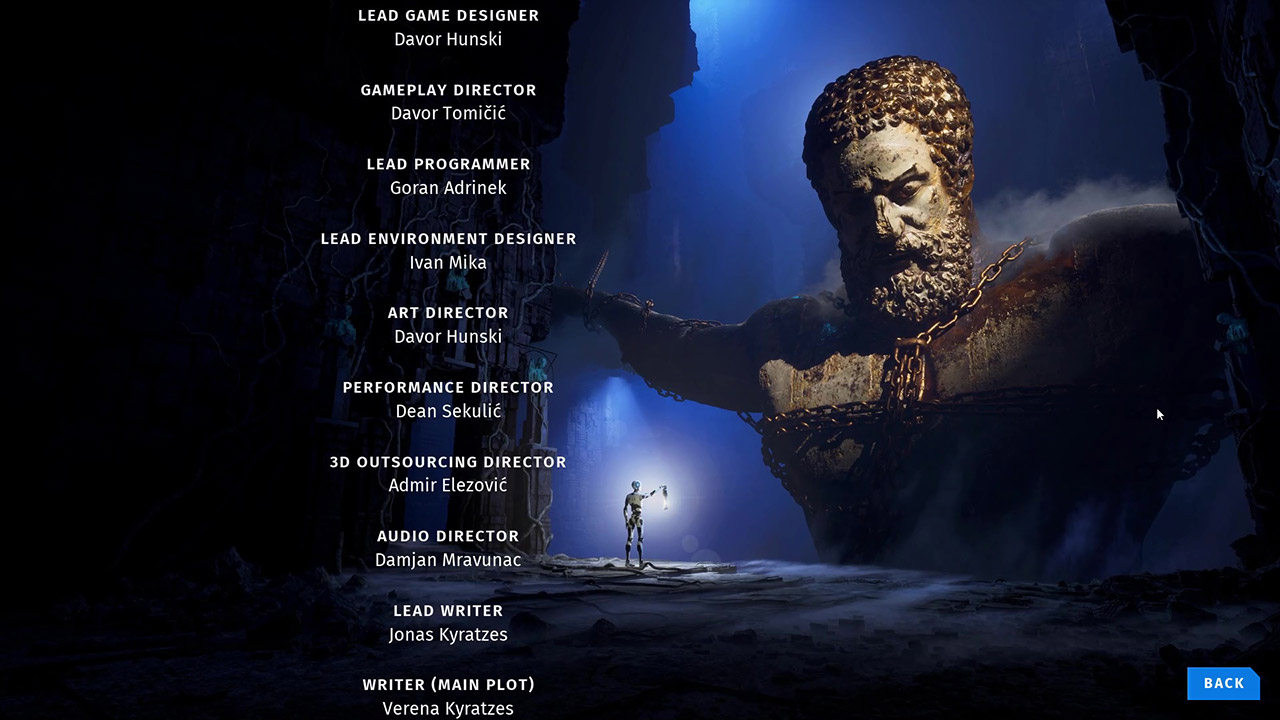

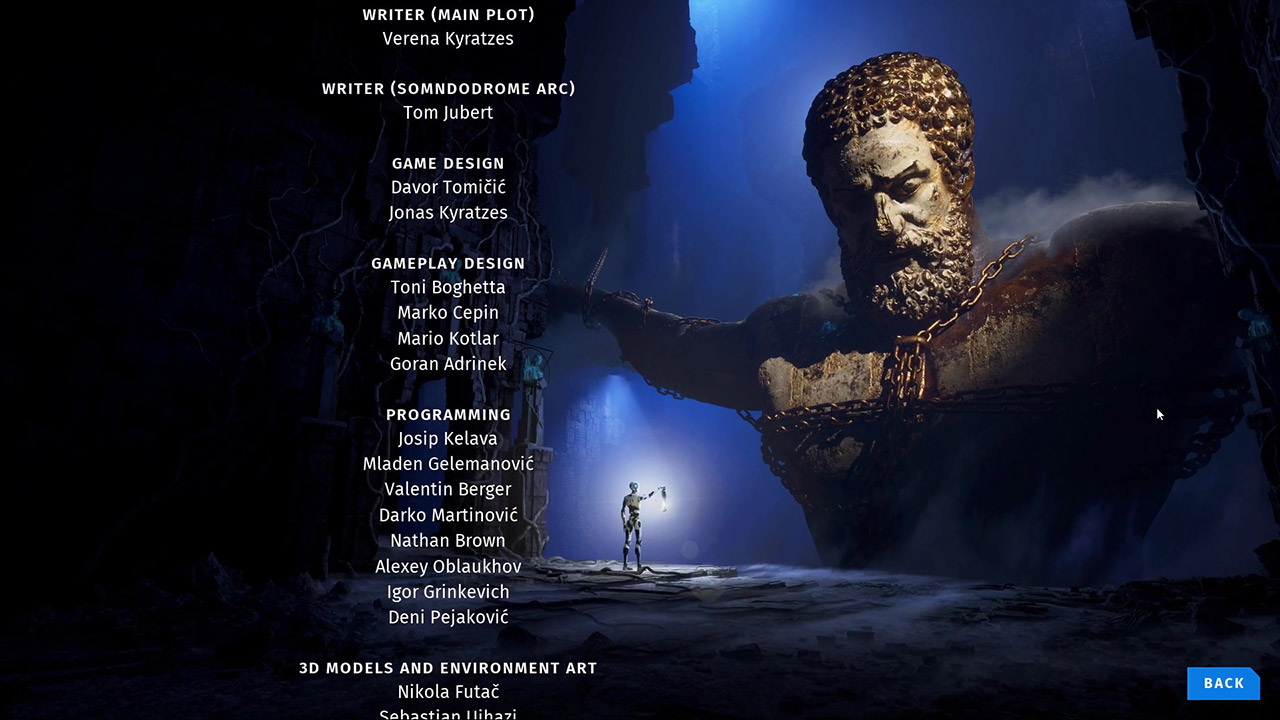

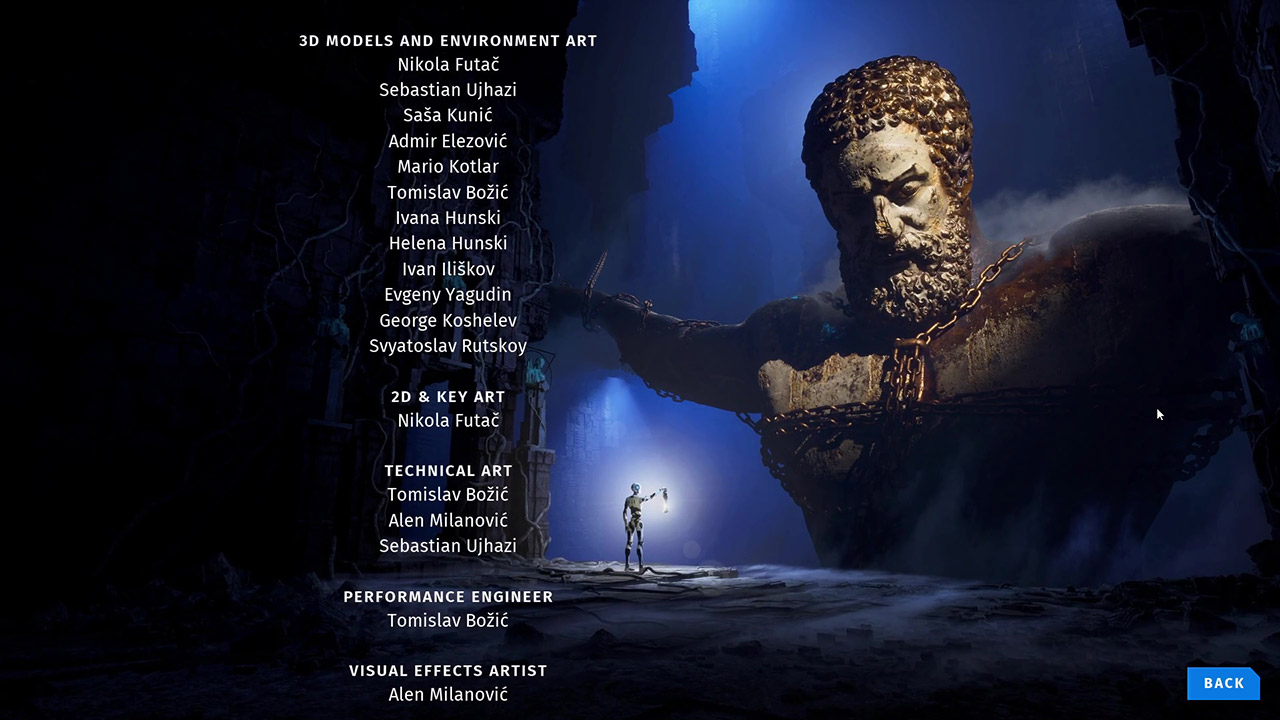

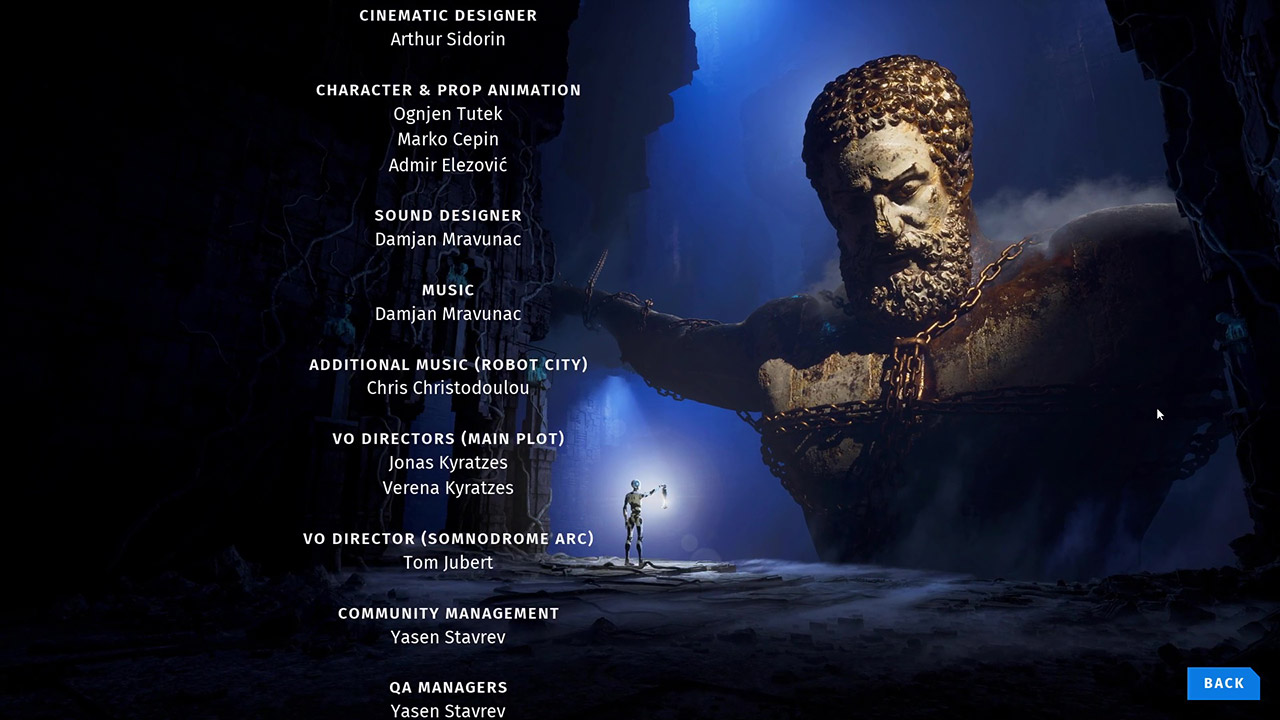

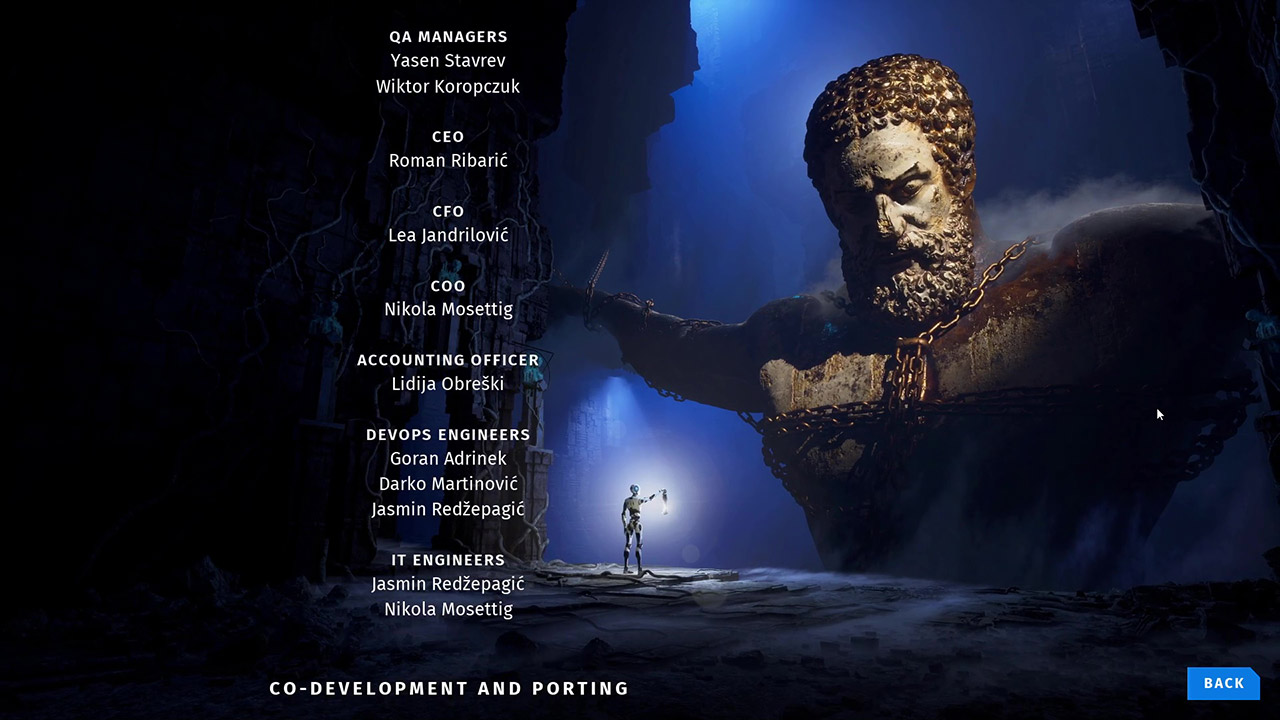

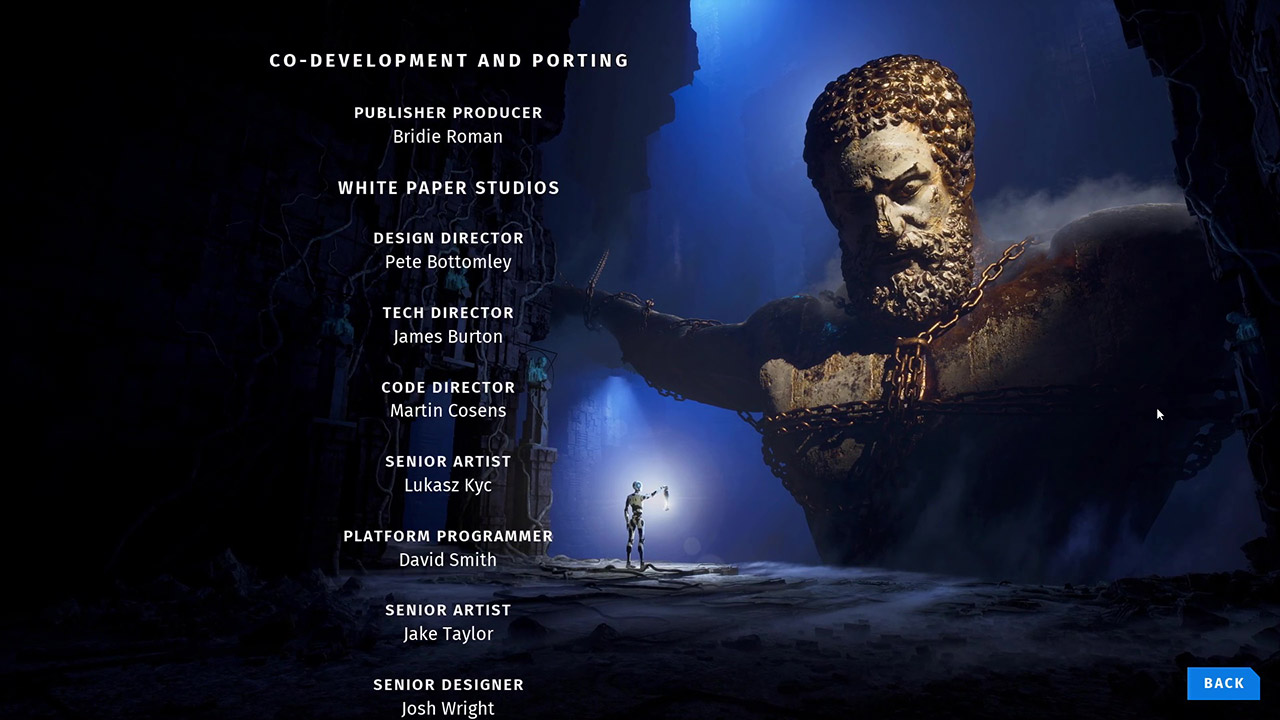

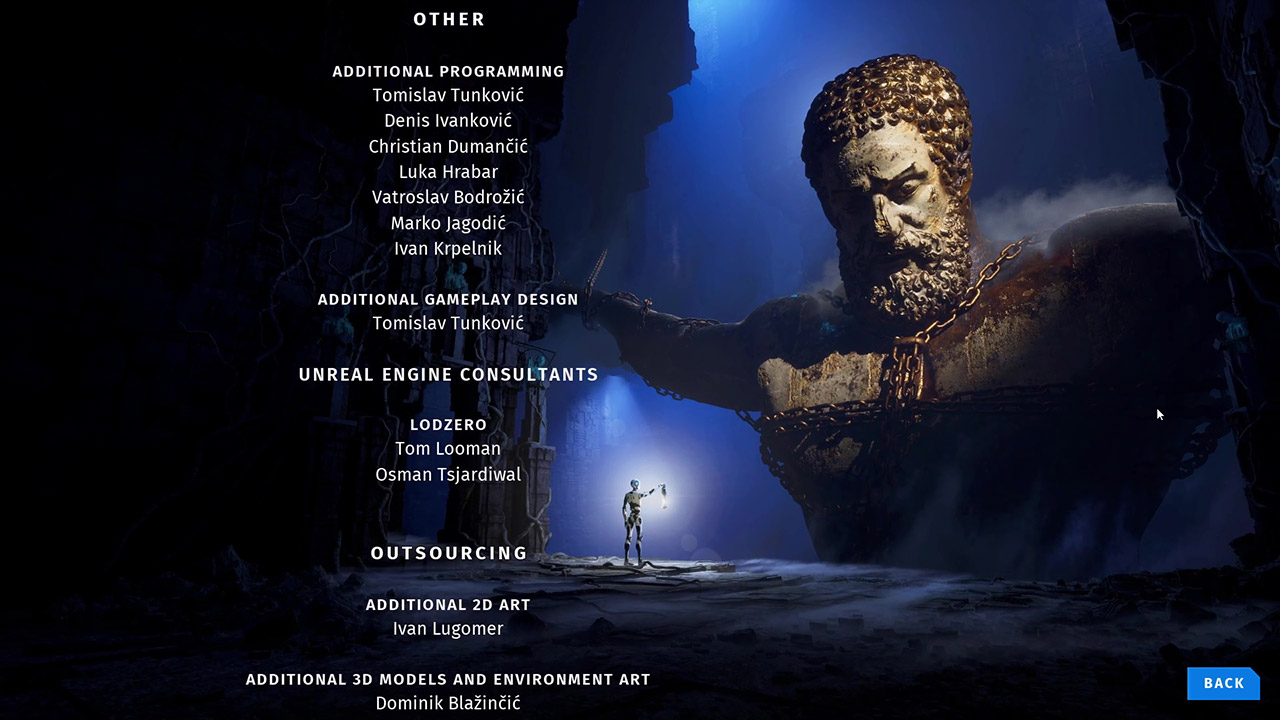

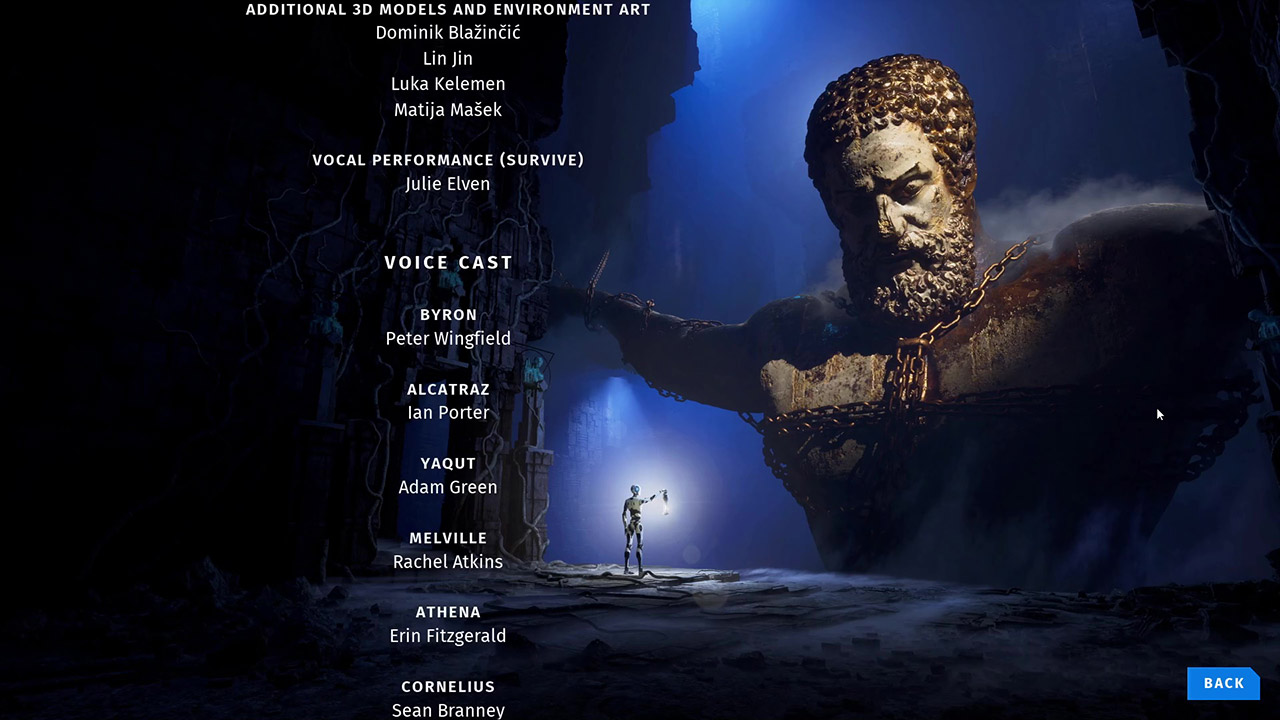

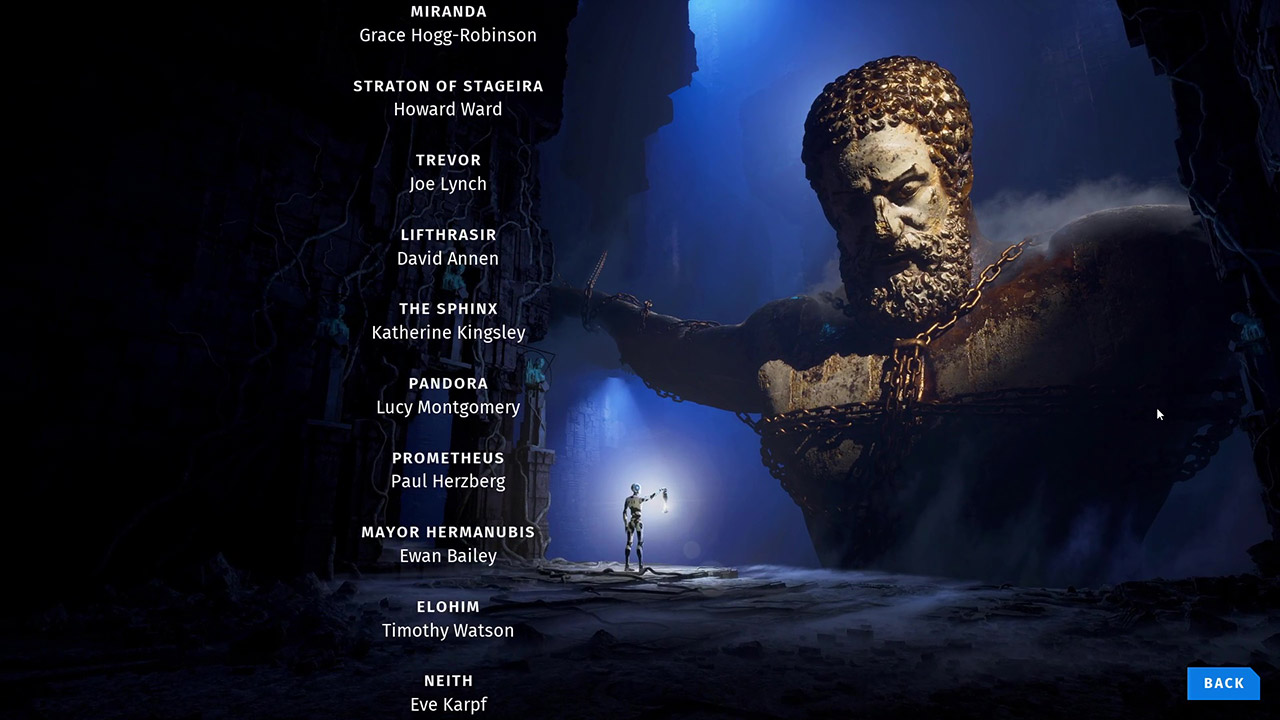

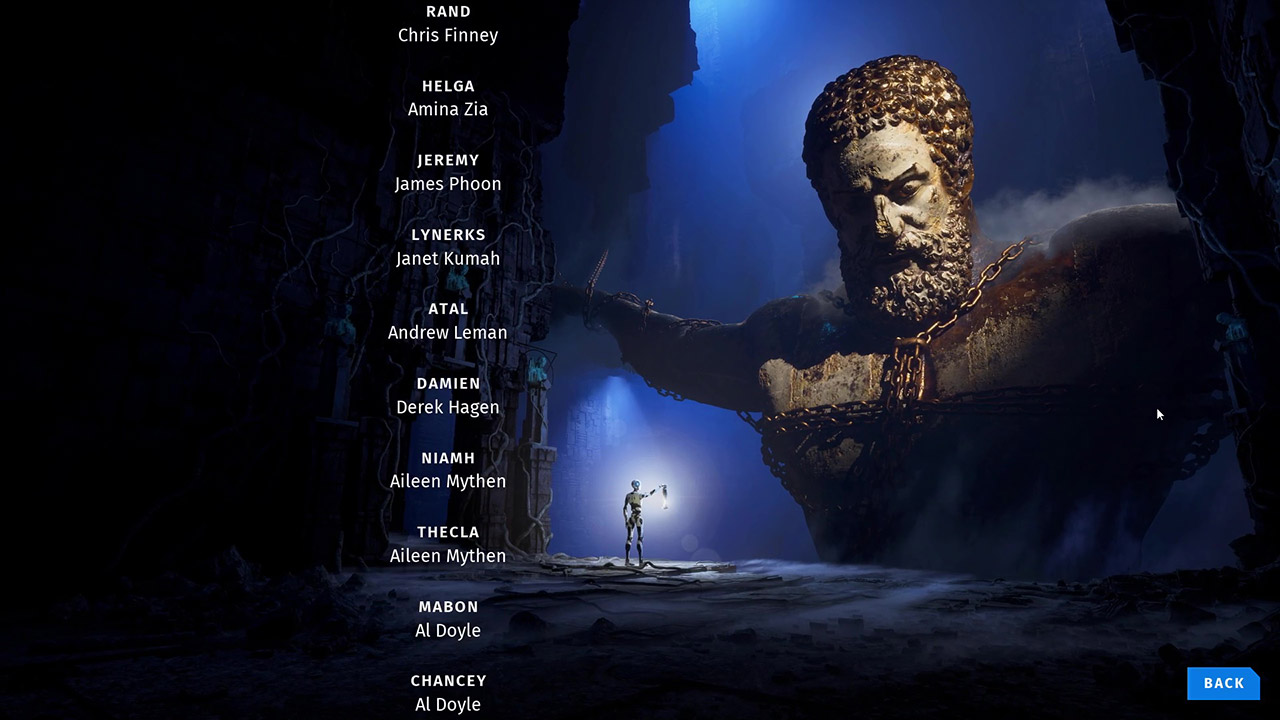

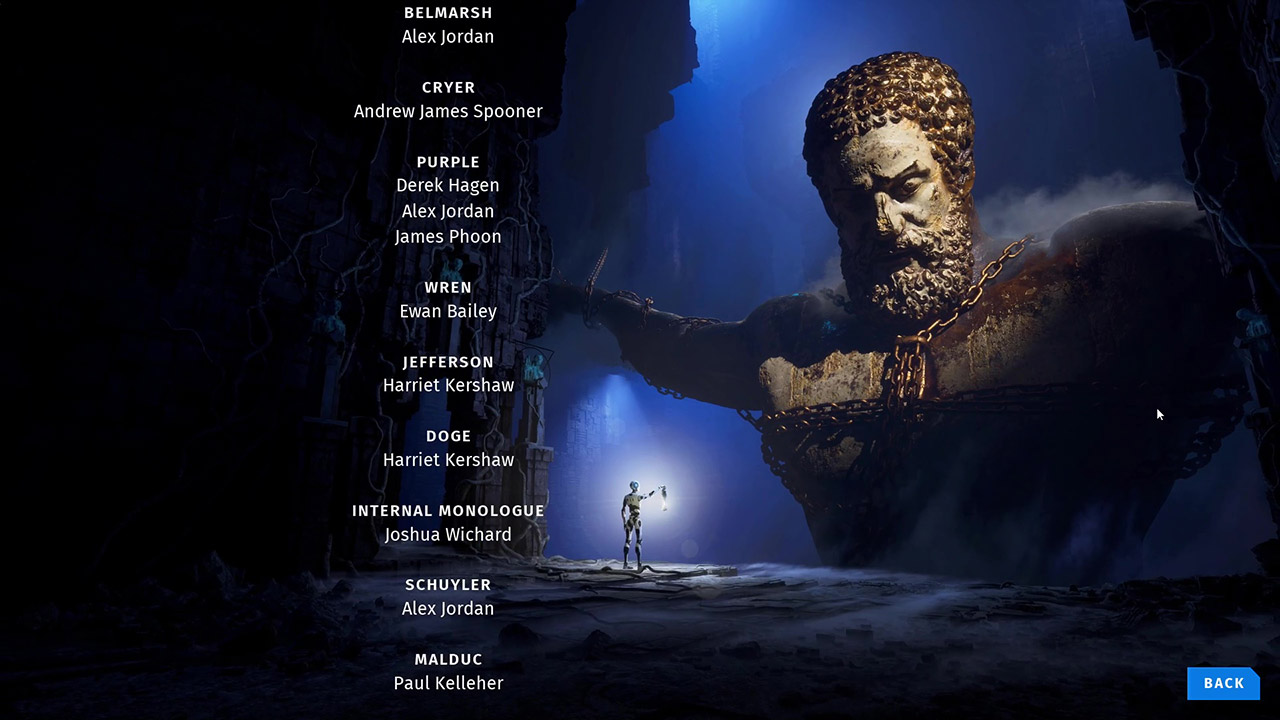

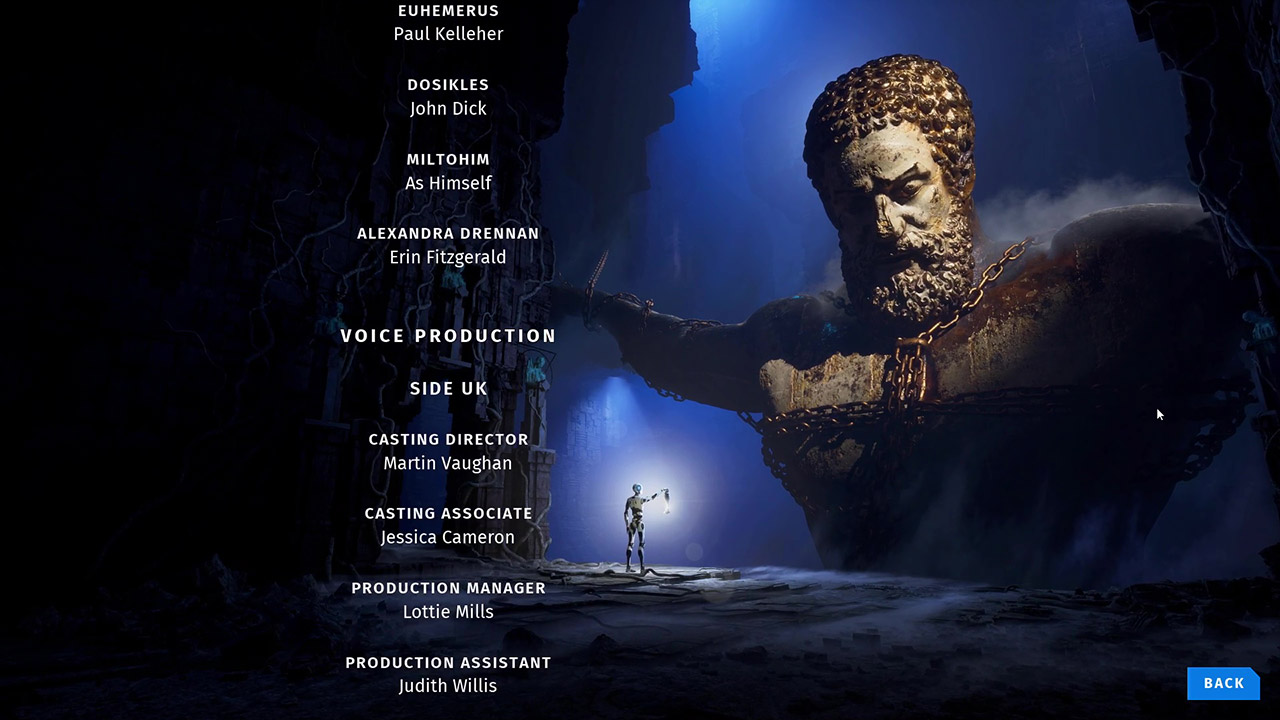

Credits

going deep down

going deep down

Introduction

As I write this (it's the beginning of July 2025, I've started early!), you are about to find out how much I LOVE The Talos Principle franchise.

I played the first chapter a year after its release as an early Christmas present, after seeing the trailer. At the time, it seemed like the most beautiful game in the world.

And I'm not lying.

It had everything I liked: science fiction, androids, philosophy, puzzles, beautiful environments. All for the very honest price of about twenty euros.

I played the base game first, then I devoured Road to Gehenna.

It kept me glued to the screen for over 100 hours of gameplay. It took me almost a month to finish everything, except for the stars (which I partially completed) and the co-op achievements. I took tons of screenshots (photo mode was generally little more than an idea in the world of video games back then) that I still have somewhere.

My ADHD was hitting hard even back then, and with other hobbies piling up, after finishing it and trying hard to find all the stars with relative success, I moved on. And like many other things, I forgot about it despite my love, caught up in other hyperfixations.

Years later, my winding journey with Relaxing Gameplaid began, also hampered by my ADHD. Talking about The Talos Principle is always there, in my head, but it's a beautiful game, and there's so MUCH to say.

Months pass, years pass, until I suddenly discovered that after a good TEN years, the sequel was about to come out. It was a matter of less than two months. PANIC. And, as always, I had postponed my desire to talk about the game every single time. Now it was late.

Could I manage to do a full gameplay of the first one, including the DLC, edit and publish everything, maybe even some guides? It wasn't impossible, but it was madness. I could publish video solutions, though.

I started recording, but I couldn't get the playtime I wanted. I had other reviews to do for games that were given to me for free, which I also needed to write and record.

The Talos Principle 2 comes out, and I haven't published a single word or video. I buy it on day one. I start playing it AND... another sudden and uncontrollable hyperfixation hits me on the head, stunning me for a year and a half, along with tabletop role-playing. After just over six months, Road to Elysium, the sequel's DLC, is released.

New panic, new stress.

I recover and start working on the new version of Relaxing Gameplaid, which takes me months instead of weeks. In the meantime, I play The Talos Principle II's main story, but Croteam has already delivered Road to Elysium.

In April, The Talos Principle Reawakened, a remastered and improved version of the first one, comes out.

Panic? Yes, but we're obviously past that level now.

After ten years of silence, the game suddenly underwent a maelstrom of unexpected new releases, hitting me with a stick and reawakening my extreme love for it.

So, and I promise I'll stop now, I've decided to dedicate myself heart and soul to talking about this franchise for a while, starting right with The Talos Principle II review. And who cares if I'm late on everything; you can't go back, and it's nice to look forward.

We'll get to the first one later.

So, I hope someone might enjoy this adventure.

SPOILER

For this reason ONLY spoilers for the sequel will be hidden and NOT those for the first chapter.

Story

Ok!

At the end of The Talos Principle, we left our Child literally being born into a world where biological humanity is a faint breath in the storm of history and time, and only their spiritual and technological legacy remains. A legacy of which this first android is, in a certain sense, the apotheosis.

A sentient artificial creature, the last of the incalculable number of iterations that took place within the Simulation, and the first to emerge from the infinite sea of failures formed by those who preceded them. Failures largely due to the active efforts of Elohim, who was reluctant to cease existing.

And at that moment, the "Child" found itself projected into a tangible body within a physical world, living as a consciousness in the former and as an inhabitant in the latter.

This is where the first game stopped; it explored the sense of self, individuality, morality and ethics, what makes a person a person, singularity, and the boundary between humans and machines.

In this sequel, we go a step further: we discover that the "Child," along with the first 12 born afterward called "First Companions," gave rise to a city, New Jerusalem, and a "Goal": in order not to fall into the same errors as their predecessors, they must be self-contained, keeping the community within a certain number. This number is set at one thousand "New Humans."

Upon the birth of the thousandth, the city will be complete, and growth will be halted.

At that point, the Child disappears, leaving the nascent society to create saints, martyrs, and sinners, and to fight for the missing resources, the increasing problems, and the citizens who are increasingly divided by opposing opinions and emerging currents of thought—between those who want to go beyond the Goal and those who consider the idea inconceivable, if not almost a heresy that goes directly against the supposed will of the firstborn. Because, yes, some people murmur that the Goal has been misinterpreted.

Time takes its course and our new character arrives: 1k, "The Thousandth," the incarnation of the Goal, the last one who, despite himself, will come into the light right during a phase of growing crisis and subtle political movements.

On the day of his birth, however, right during the mayor Hermanubis' speech, something unpredictable happens, and a strange, incorporeal projection presenting itself as "Prometheus" tells them to go to a mysterious island, before being forced to flee from the aggression of another entity called "Pandora."

And in the blink of an eye, 1k will end up taking part in the expedition that will go to explore those territories, to try to understand what on earth could have happened and what is found there, and at the same time, what the best destiny for New Jerusalem is.

Thus begins not only a geographical journey with 4 other "New Humans," but also a new adventure within philosophy, just as it was in the first chapter.

Back then, we answered "What is an individual?" now it is time to answer, ""What is a civilization?"

Visual Style

Ok!

Quality and Graphic Engines

Between the first game and this sequel, nine years have passed (December 2014 - November 2023), and a lot of water has flowed under the bridge of technology, including video game technology.

The first game was developed with Croteam's proprietary graphics engine, Serious Engine 4, which I believe was still normal at the time, at least for those who could afford it. The second, however, was developed with Unreal Engine 5.

After all, the great "democratizing" graphics engines—those that truly made indie video game development accessible to almost everyone—emerged in the early 2000s, gaining strength around 2010. Leading them all are Unity (used mostly for 2D and mobile games, being free and easy to use, royalty wars aside), Unreal (which for a long time remained a staple of AAA studios but then saw a wider use), and Godot (perhaps the least used until relatively recently).

Graphically speaking, The Talos Principle at the time left me speechless from start to finish (obviously I won't tell you how much I loved "The Land of the Dead"/Ancient Egypt), and the visual aspect was certainly at least a third of the reasons why I fell in love with the game.

And why my PC filled up with screenshots.

Damn them.

The 2014 graphics won me over with the immensity of details, made possible by the on-site scanning of real archaeological structures, which were then transported into the game engine. Consequently, the shapes and textures were not created and adapted from scratch trying to be as faithful as possible, but reproduced and imported from reality.

A process not necessarily easier, but one with an undeniable visual impact.

This sequel, however, sees the transition to Unreal Engine 5 (released in 2022) after starting on UE 4. This makes some aspects of rendering more effective and easier to manage through systems like Lumen and Nanite, such as the construction and lighting of large areas, which would otherwise be difficult with pre-rendered lights or the old proprietary graphics engine.

Croteam, in fact, abandoned Serious Engine in 2020, after Serious Sam 4, making The Talos Principle 2 the first of their games developed with Unreal.

And the result is, for me, exceptional: the graphic and atmospheric continuity of the first game flows without jumps or jolts into the second like a mountain stream and with the same freshness, proposing once again the wonderful and vast abandoned landscapes, which go from being historical in TTP to natural in TTP2. This not only offers us graphics that keep pace with recent times, but which, in-world, also conveys very well the transition from the Simulation—a world that only exists inside a computer system—to the real world.

The Simulation, after all, didn't necessarily have to be at the incredible level of deceptiveness of The Matrix, but a credible world in which to move AI iterations that were never human and that were born and disappeared within it without having terms of comparison with the "true" reality.

In short, it wasn't important if the way light bounced was perfectly plausible or if it created unrealistic artifacts—and no, there weren't any—(though the distorted glitches in TTP—obviously intentional—were something I adored; they reminded you that none of what you saw existed), but here, in the real world, it makes perfect sense to have sought the best way to create much more realistic environments with more modern development engines.

~°~

Design

As we said above, the pillars of the first game's environmental graphics remain, despite a different graphics engine and setting.

And the design?

One of the first things we encounter is the renewed design of the robotic body, and here I have to divide my opinion in two: visually similar to the previous one and very beautiful, it is, however, more advanced and decidedly closer to the original anatomy of human beings. The amount of detail is remarkable, and even though the New Humans are structurally all identical, the variety of colors they have is a simple but effective trick to differentiate individuals.

In TTP, we are alone, with the only exception of The Shepherd (golden) and Samsara (light blue) in the final tower of the base game. The color of The Shepherd, or something very similar, will be used again in Road to Gehenna for all the imprisoned iterations.

On the other hand, however, I have to admit that I loved certain aspects of the first body, such as the feet (no easy jokes pls!): they had two toes and a "heel-to-toe" that served as a shock absorber without the desire to faithfully reproduce the corresponding human part, only to replicate its functionality. In TTP2, however, we find normal feet, and a body designed to much better imitate human proportions.

However, even as a lover of strange things, monsters, and artificial creatures, I understand that from an in-world point of view, the New Humans may have desired bodies closer to their ancestors, instead of structures that might be more efficient at the cost of less "humanity."

Assuming this is really the reason, of course, and not something more structural, but as you know, I love to snoop around in the world-building.

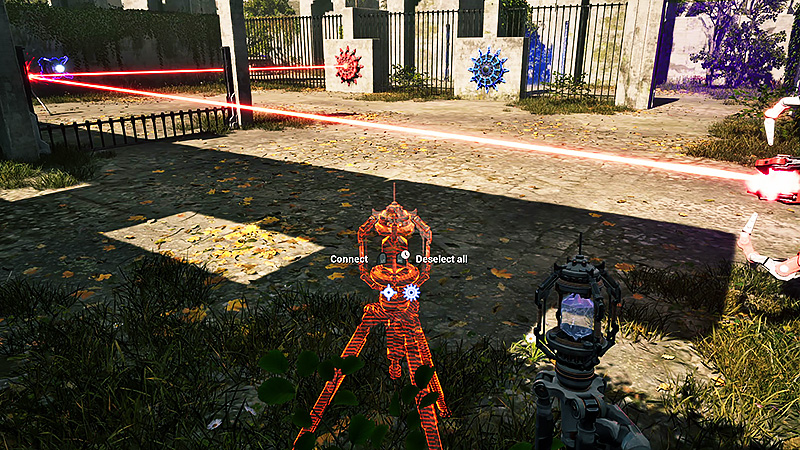

Another feature of this sequel is the Megastructures: gigantic constructions with complex and complicated shapes, one for each of the twelve sub-areas, which are accessed once the eight base puzzles are completed. Extremely different from one another, in my personal opinion, they are all breathtaking both in rendering and design. The fact that you can walk around them and even end up underneath them even before completing the puzzles allows you to understand how truly enormous they are, raising more than logical questions in the mind about how they were created.

Even the environments that host them are very well-cared for and truly immersive in imitating the natural biomes they represent. I greatly appreciated, here too, the high level of detail, the care in mixing wild and seemingly uncontaminated nature with artificial constructions that look artistic and abandoned, which in a completely different yet similar way manage to evoke a feeling of solitude and mystery close to what happened in the first TTP.

After all, apart from 1k and occasional encounters with the other team members engaged in their explorations, there is no one else: just animals, puzzles, terminals, and other things scattered around.

All the macro-areas and the three connected sub-areas become increasingly intriguing up to the last ones, where beautiful giants of sculpted stone lie as far as the eye can see or where the immense inactive spaceport dominates.

You have no idea how many screenshots I've taken.

Damn them twice (╯°□°)╯︵┻━┻

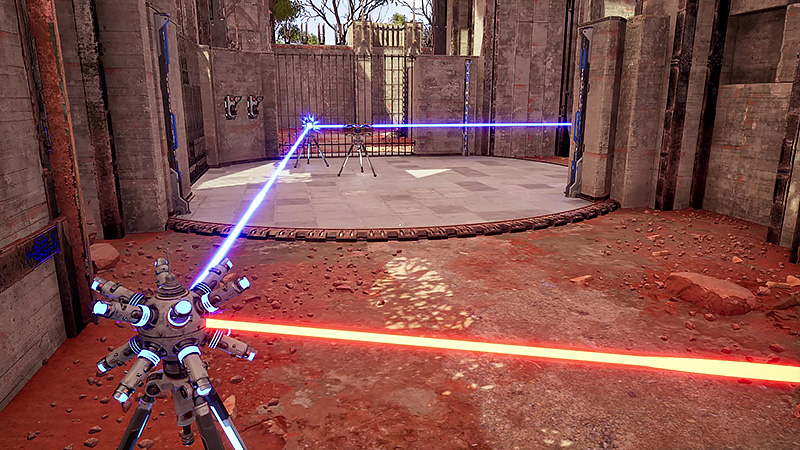

Even the re-design of the surviving TTP devices and the new ones introduced is well homogenized: the former are updated without becoming alien, the latter are presented perfectly in line, blending well also in use.

Except perhaps for a couple of mechanics counted among the novelties of this sequel that are very different from the rest, everything works in a similar way to what happened in the previous game. However, even in TTP, if we want to be strict, the same thing happens: the temporal holograms towards the end of the game, for example, were a rather different dynamic from what had been seen up to that point.

~°~

Not-so-brief excursus (as if I didn't do enough already...).

I found players complaining about some differences in effects in the interaction with the environment between the two games which, although I recognize that they actually exist, do not seem to me as dramatic as they tried to make them out to be, nor a matter over which I would raise a fuss.

I admit that playing in the first person, I didn't even notice the two things until I stumbled upon these discussions, and even now that I am aware of them, they seem completely secondary and not at all obvious at the gameplay level.

Specifically, I found two main references:

- the "bounce" of the blue barriers when the character bumps into them.

In TTP, there is a very visible wave, as if the energy field creating the barrier were somehow elastic rather than a solid "wall." The idea it gave when bumping into it was that we were bounced back and not simply stopped by a rigid and immovable obstacle.

This doesn't happen in TTP2. The barrier is motionless, and when we run into it, there is no reaction whatsoever.

- the interaction of water when walking or passing through it.

In TTP, when you immersed even just your feet in any kind of water collection, and in particular the shallow stone basins, it reacted to the passage very realistically.

In TTP2, again, it doesn't happen. The water effect appears decidedly more limited.

As I write this, I haven't investigated thoroughly to understand if this is just how it is or if it perhaps depends on collateral graphics settings, BUT, even if it was intentional, I reiterate that my opinion about the entire game does not change. Beyond the fact that most of us probably play in first person and rarely pay attention to these things, not being an RPG, I would say that the quality of the gameplay does not worsen.

Personally, regarding the blue barriers, I prefer no effect to the previous effect, which made it more complex to approach to see what was beyond, due to the waving. A very light reaction and sound might have worked, but this is perfectly fine too. For the water, however, I consider the effect sufficient, because I play in first person and almost never look at the ground. But I understand that others might prefer otherwise.

Would I like to know the reason? Certainly, I love behind-the-scenes stuff.

Maybe we'll discover that it's not simple laziness as hypothesized, nor a lesser effort in development, but something technical due to the transition from Serious Engine to Unreal that they couldn't overcome. Or a stylistic choice to introduce fewer distractions. A way to keep the graphics, which are already extremely rich in detail, lighter.

Or maybe not, and it's simply a deliberate choice.

Game Mechanics

Ok!

Regarding the mechanics, this sequel also manages to maintain an extraordinary continuity with the previous chapter, eliminating some, keeping others, and at the same time introducing completely new ones.

One could say that it retains the most basic and iconic ones, without which it would have been difficult to create another million puzzles without reinventing everything from scratch, while livening up the gameplay and curiosity with new features to stimulate players who have already faced an endless sequence of puzzles in the first game.

The game initially projects us into an environment that serves as a bit of a starting zone and a recap of the first game, but also and above all, as an introduction to what will come shortly. From this moment on, everything is perfectly integrated into the lore: in fact, it is the "booting zone," the "birth" process of the New Humans.

While we refresh our memory on the mechanics using the old devices (but already with the new android model!), we hear the voice of ELOHIM guiding us again and explaining where we are, why, and what awaits us. We will also find the gates to be solved with the tetrominos pieces earned from the puzzles we have completed.

Let's start by saying that the puzzles and the methods for solving them are truly very similar: as mentioned above, there is obviously a story that, as in TTP, puts the puzzles and the need to solve them into the lore and unfolds across multiple different areas. In each one, a new mechanic will be introduced to us.

Second, something I only started to notice at a certain point, when the curiosity and novelty faded into familiarity, is the absence of all those hostile entities we had in TTP: the explosive spheres and the machine guns to deactivate, avoid, or jam, and so on.

Herei, nothing tries to threaten your life ibecause there is no need.

However, the lack of threats does not create a boring environment, devoid of mysteries and without challenges—quite the opposite. Simply put, in the Simulation, as a simulation, there was no problem with blowing up every two steps, as they were pixels, but in tangible reality... how to put it... exploding has consequences that are a little more complex to remedy.

The game is divided into four macro-areas, one for each cardinal direction, which are in turn divided into three sub-maps, each represented by a different Megastructure, and are, in this order:

EAST

First area of the game,

E1 - Grasslands Ring

E2 - Wooded Plateau

E3 - Eastern Wetlands

NORTH

N1 - Desolate Island

N2 - Flooded Valley

N3 - Lost Marches

SOUTH

S1 - Southern Coast

S2 - Verdant Canyon

S3 - Circular Oasis

WEST

W1 - Western Delta

W2 - Anthropic Hills

W3 - High Plain

Each of these three sub-maps is characterized by eight regular puzzles and explicitly marked extra content in the map hub: two additional "Lost" puzzles similar to the regular ones, one hidden lab, two monuments, and the "Golden Gate" puzzle. The latter is only accessible after completing all twelve sub-maps, practically at the end of the game.

Further content, both overt and signaled by the "compass" at the top of the screen (if active) and hidden, are: scattered terminals that offer various content (signaled), the holograms of Straton of Stageira, the human artifact, the manifestations of the past (the latter represent scenes of human history, elements of the Simulation, or TTP in general), Prometheus' Sprites (currency necessary to use the "Prometheus terminal" within the puzzles and skip them).

Upon completion of each puzzle, a cloud of particles is released, which represents a "token" for access to the Megastructure dominating the area. This is earned after solving the eight base puzzles and constructing a bridge with tetromino pieces. Once the bridge is complete and the Megastructure is visited, a laser will be activated.

Once the three sub-maps of a macro-area are completed and the lasers in the three respective Megastructures have been activated, access to the central Pyramid will be granted with the possibility of further exploring the history and lore.

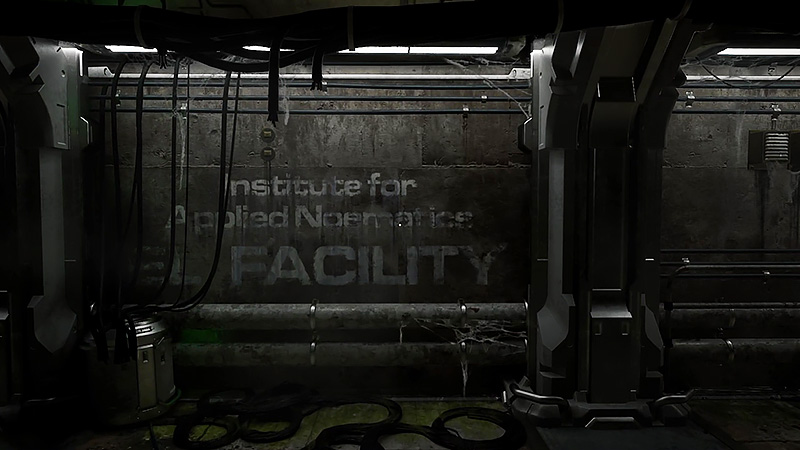

Returning to the topic of mechanics, as for what returns/remains we have: the old connectors and jammers, the blue and purple barriers, the hexahedron (the cube), the fans (of all types, from fixed ones to those with a removable grate, from those that lift you up to those that blow against you to prevent you from advancing, etc.), the wall switchers to activate/deactivate barriers and devices, the big square red pressure buttons.

Speaking instead of the new ones, I'll leave the list here.

Given that this second chapter, unlike the first (which had full Italian available, including voice acting), doesn't even have the interface in Italian, I will leave the names in English.

RGB Converter: the first of the new dynamics presented to us, it is a device that combines two lasers of different colors and returns a third output based on subtractive and additive principles: red+blue=green, green-blue=red, green-red=blue.

Driller: it is a device that allows you to open breaches on specific walls. Other devices and laser beams can pass through the opening, but not 1k natively.

Inverter: a device that inverts the color of the laser directed at it. It only works with the original blue and red lasers, not the green one.

Consciousness Transfer: literally. In some puzzles, one or more bodies identical to 1k's will be present, into which one can transfer in an instant and take control.

It is not possible to move simultaneously, so the dynamic is different from the temporal projections of TTP.

Note: one thing I adored is that they put the existence of this mechanic into the lore.

Accumulator: as the name suggests, it is a device that accumulates the energy of a laser and allows you to have a "portable" independent form of it.

Switcher: it is a collateral mechanic, where a table offers a useful device that can only be taken by delivering another one in its place, as it cannot remain empty.

Teleporter: it is a small portable platform, onto which 1k can teleport, albeit only through free areas, bars, driller breaches, purple barriers, and the like. Solid walls and blue barriers, for example, do not allow it.

Gravshifter: perhaps one of the most interesting dynamics. It is a gravity inverter capable of creating a unidirectional attractive beam, which allows 1k or a device to be pushed towards walls or ceilings. When exiting the beam, it falls, however, unless anti-gravity surfaces are present.

Anti-gravity Surfaces: often in combo with the Gravshifter, these are walls that allow 1k to move and devices to be positioned against walls or ceilings without falling. This opens up the possibility of moving three-dimensionally as would happen underwater, not just horizontally.

Levitating Platform: these are suspended circular plate platforms, capable of following a predetermined and unchangeable path when connected to a laser and of transporting devices or 1k.

Activator: it is a peculiar device that, when connected to the laser emitter with which it shares the color, creates a dome field. Underneath or in contact with this field, it is possible to activate—precisely—one or more devices, including other activators, or deactivate others like the blue barriers, as long as they remain in contact or under said dome.

Soundtrack

Ok!

As we well know, music is a vital part of any audio-visual work of any genre. A well-made or terrible soundtrack can contribute significantly to the success or failure of said work.

In the first chapter, the music, in my opinion, is at least half of the experience, and quickly, puzzle after puzzle, in each of the three macro-areas, it becomes familiar and a companion on the adventure. These are precisely the pieces that, if heard outside the game, don't take long to recognize and associate with TTP.

And in the sequel?

First of all, we find the same composer of the first soundtrack, Damjan Mravunac, a long-time composer for Croteam, also for the Serious Sam IP. This ensures a special continuity with the first chapter.

In fact, similar to the first soundtrack (also released on Steam), we find 44 tracks, a large part of which will be repeated without becoming heavy over the long hours of gameplay and will probably remain recognizable even once you reach the end. They are constantly cycling in the background, and some are specific to very precise events (for example, there is a theme for the VTOL flight, one for entering the Megastructure at the end of a sub-area, one for when you bring the flame back from Prometheus, one for visiting the labs, etc.).

The soundtrack also opens with an iconic old piece from the first game, now somewhat the IP's theme: "When in Rome", which, revised and modernized for the new adventure, becomes "Once in Rome". It's absolutely the same piece, but less "background" and more "presentation," a little faster, more "technological," and expanded.

One difference compared to the previous soundtrack is that for the first game, we were offered 30 tracks and an alternative version of 13 songs, while here all 44 are equally present in the game, without alternative versions of any kind. This is understandable, considering the presence of many more areas, more interactions, cutscenes, and a generally more complex story.

Other

Playtime: at the end of the game, the progression summary tells me approximately 70-something hours.

Performance: excellent. I started playing when I was still using my i5-4440 from 2017, and even though I experienced visible slowdowns and tearing, lightening the graphics made it quite playable, but I find it hard to keep the graphics low with such beautiful landscapes.

As fate would have it, I suspended the game a few days after its release, only to resume it in 2025 with the new processor. From there, it was all smooth sailing!

Bugs: apart from a few minor bugs in the very first days after release, which I assume were immediately corrected, I only had a couple of crashes very far apart, probably due to my PC. Once I replaced the processor and motherboard, everything went smoothly, and I only encountered a few glitches (like a fox found running in circles in mid-air).

Notes

Motion Sickness

As is known, I tend to suffer from motion sickness quite easily, but like everyone who suffers from it, the degree and effects vary widely based on the individual and the game.

TTP2 has an entire section dedicated to Motion Sickness, with an excellent range of options that, all together, allow you to highly customize the experience based on specific symptoms and mitigate them as much as possible. We see them below:

Field of View: allows you to change the breadth of the field of view.

Motion Blur Strength: modifies the intensity of the blur of the field of view during rapid movements

View Bobbing: enables/disables a system of camera micro-movements that increase immersion

Carriable Item Bobbing: enables/disables the swaying of objects when held in hand

Ignore Base Rotation for Camera: enables/disables camera rotation when on rotating platforms

Preferred View Type: allows you to choose between first and third person

Third Person Camera Alignment: allows you to choose the right or left shoulder for the camera

Instant Gravity Change: Instant Gravity Change: skips the transfer animation to/from a gravitational surface, making the movement immediate and avoiding the rotation of the field of view

Player Speed: allows you to choose the character's movement speed

Mind Transfer Camera: determines the camera view after transferring from one body to another

My Thoughts

Ok!

Attenzione Spoiler!

Personally, I side with those who say that The Talos Principle 2 doesn't have the same "magic" as the first one, that Milton's absence is felt, that the exploration of the areas—aware of being completely alone, but at the same time having no idea what the puzzles are, what they are for, and exactly where solving them leads, with all the moral questions that arise—makes the experience very different.

TTP is an extremely solitary experience, with the only company being the distant echoes of past iterations in the form of QRs, messages in a bottle entrusted to time and filled with moral doubts, uncertainties, and delusions of faith. Iterations of which, at that moment, one couldn't even have an idea what had become of them, and I believe we all imagined them destroyed by ELHOIM or the system for having failed.

Even the messages from Alexandra Drennan, the mind behind the project and our drive to continue, were a romantically melancholic experience veiled in bitterness, conscious that she, like all her colleagues, had been dust lost to the wind for centuries. Different from finding recordings in the current terminals, whoever they belong to, apart from Trevor, though equally interesting.

The same thing happened in Road to Gehenna, where the interaction among the imprisoned iterations (excuse the pun) was different, more collateral and, as far as I remember at least, not "direct" as we have it in the sequel. Communication remained an activity constrained to writing on terminals, in a community we had to free in a race against time while the Simulation was falling apart. No face-to-face dialogue.

But The Talos Principle 2 is NOT The Talos Principle.

It seems obvious, yet it isn't: as I see it, you can't compare two video games, one the sequel to the other, on such different topics and settings and hope to find more parallels than those desirable and necessary.

Just as we cannot go back in time, to play this chapter as if we had never faced the first one, to feel the flavor of that wonder again. Because, my friends, unfortunately, this is what creates much of the "magic" that we then become nostalgic for (and makes some annoyingly critical when there is no need).

So no, TTP2 doesn't have the same magic as the first one. However, it has its own, different one, and you might need to be patient to feel it.

Let's instead rejoice that it is not a second chapter made exclusively to push the franchise forward or to renew the gameplay as if it were a simulator (in the various The Sims, Tropico, Farming Simulator, or City Skyline, it makes sense, despite sometimes succeeding with dubious results), patching together a shoddy and crooked story just to hold things together.

The Talos Principle is a story, in my opinion, well-constructed, unexpectedly touching in the most human sense of the term, original in its world-building and way of telling the story, and yes, even in its non-originality in terms of archetypes and tropes. It has a rich lore, with high and sharp steps, which serves to make us rack our brains not only with the puzzles but also and above all with the questions.

In the first chapter, we explored what an individual is; here, we explore what a society is. Two concepts intrinsically interconnected, but absolutely not overlapping or comparable 1:1.

Furthermore, it leads us gently into a deep dive into what it means to be part of a community: the desire for connection with others, desires and feelings, expectations, anxieties, pressures.

We see this especially in the story of Athena, both as the "firstborn" and unwillingly transformed into a "Founder," and as Cornelius's companion with her (their?) desire for family, even driven to the point of trying to create a new life outside the system that the IAN left behind.

A 360° deep dive into the New Humanity that has been forcibly left its biological origins behind and had to embrace artificial ones and a synthetic body.

Beyond my very personal soft spot for Melville, which can be inferred from my longplay videos, I admit I liked all the protagonists and even the collateral characters, some more than others.

By "liked," I don't necessarily mean they were to my taste, but they were well-written, coherent, and had an understandable place within the narrative. As a lover of world-building, I did not find poorly written, two-dimensional, gratuitously or unjustifiably stupid, or unbearable individuals.

Each of them has a strong personality, which easily emerges in all the interactions the game offers, thanks also to the extraordinary work of the voice actors. They have given a unique voice to each of the main characters, conveying their character, their uncertainties, and their relationships with extreme naturalness.

I found honest pleasure in hearing them talk even among themselves.

The fearful caution of Alcatraz, traumatized by the fate of New Alexandria and the loss of thirty people to the point of viewing every step forward with suspicion and finding solace in Hermanubis's immobility; the enthusiastic push for progress of Byron, which puts them in contrast, so strong that it casts some shadows on him (like in pushing the reconstruction of New Alexandria: was it the fear that stagnation would grasp everyone, or was it insensitivity to suffering?), then discovering how abandoned he feels by Athena, who disappeared without telling him anything; Melville's desire to break out of New Jerusalem's energy impasse and resource scarcity to make everything work (since materials for bodies and their maintenance are also scarce) and to explore the power of engineering when placed in their hands, which makes her sensitive to the power of what they discover on the island and to Byron's ideas; the purity of Yaqut's curiosity, his uncertainties and his manipulability that make him swing between Byron and Alcatraz—all of this makes the plot truly plausible.

But it is also interesting to see the faith that Hermanubis clings to and with which he infuses all his convictions, certain of doing good by maintaining the Purpose, with his followers who follow him in an apparently blind and zealous way, helping to understand the nascent "power" dynamics. Or the dramatic desire for family of Athena and Cornelius and the tragedy that struck them, positioning the former, especially, on an extremely high level of humanity. Not to mention the rational hope that Miranda embodies, miraculous in her birth and visionary in her ingenuity, fascinated by everything in the micro and the macro, afflicted by a thousand doubts yet already perfectly aware of their possibilities.

And even when a voice actor is not present, or is heard for only one or two dialogues or even single lines, it remains very pleasant to follow them in the threads on the Interface, where often extremely interesting food for thought emerges.

This is why I am surprised that there are people who define the characters as "unlikable" and criticize the fact that they "talk": beyond personal preferences in terms of video games and puzzles in general and the two chapters of TTP in particular, discussing the game's lore, isn't that what happens every day in a society? Isn't it our daily life to deal with people we like and dislike and with whom we have relationships ranging from generic and professional to close and personal? With whom we share opinions completely or in part, or from whom we completely disagree?

Melville, Yaqut, Alcatraz, Byron, as well as Athena, Cornelius, and Miranda, but also Hermanubis and his followers or the inhabitants of New Jerusalem in general... they don't have to be likable to you.

They are not obligated to be likable to you.

Or rather, to put it a little less brutally, you have no moral obligation to like them.

They must convey the idea of a plausible community made up of literally a thousand different individuals, not be the perfect RPG with a Ghibli atmosphere or a mute list of pure puzzle levels.

Moreover, not only can we not deal only and exclusively with people we like in life, it always remains that one person can be disliked by someone and liked by someone else, which is why one cannot presume that if the characters are unlikable to one player, then it must necessarily be the same for everyone to the point of making it a criticism of the developer.

As if it were materially possible to make sure that the characters appeal to every single player.

Sure.

The characters are there in the same way that the QR codes were in TTP: to give different opinions, offer moral and ethical nuances, fears and anxieties, contrasting visions of the future, and push the player, through 1k, to understand which direction they want to explore: stick with Hermanubis or Byron? Understand or condemn Athena? Justify or accuse Cornelius? Exploit new discoveries and new technologies or destroy them? Open New Jerusalem to the world and expansion or keep it stable since "the Purpose" has been achieved?

The options are as diverse as the possible endings, but in the first playthrough that is completed, one must somehow choose one (unless you randomly pick in every dialogue and ignore this vaguely role-playing aspect, but at that point, honestly, if you hate the lore of games, I would suggest choosing those with pure puzzles without any story behind them) and carry forward your vision, ideas, and intentions one dialogue at a time.

Then, by all means, saying that you didn't like the dialogues and voices and that you would have ideally preferred a mute chapter, similar to the first, is fair. But saying that the dialogues make no sense, that the characters are unbearable, and that they ruined the game... I find that to be a blind criticism made for the sole sake of negative feedback.

New Jerusalem

I will write an in-depth article about this because there are several things to talk about and analyze in terms of world-building, and I don't want to drag it out too much, so I'll just say that New Jerusalem is... peculiar.

Although at first glance it can easily appear cold, sterile, and sparse, or even poorly conceived (and I include myself among those who had this feeling initially), as the game progresses and with the few visits during the events, it seemed perfectly sensible to me.

I mean, the "New Humans" presented to us are, in fact, androids: they don't eat, they don't drink, they don't produce waste, they don't wear clothes, they don't wear trinkets or jewelry, they don't sleep, they don't feel hot or cold, and they are technically immortal.

The only living things present in the city are the pets some have, mainly cats.

What is truly essential is energy for recharging and everything they need to complete and maintain the city's construction.

For me, it follows that their urban environment appears extremely futuristic, clean, and almost aseptic: there are no shops or kiosks (apart from Helga's), there is no garbage, and everything, from decorations to social meeting points, references the human past, the Simulation, or their cultural growth.

It's obvious that in the end, it will appear like a park without the fun, and one that takes itself very seriously.

One must also consider that the city is plagued by a scarcity of raw materials and continuous blackouts, in addition to a sense of "incompleteness" while waiting to achieve the Purpose and from there "start living for real." Or that is the feeling.

Furthermore, I was very struck by the absolutely not insignificant role of the dome over the city, which is far from being completed. It is simultaneously an ambition for those who believe in the Purpose and an anxious Sword of Damocles for those who would like to stop it.

The door to perfect existence made of containment and security, or the prison of privations, boredom, and "doing what needs to be done" for eternity.

One must also not forget that the visitable area of New Jerusalem is just a third or less of the total surface area. We only see a few small portions at the beginning, when 1k first arrives there on the capsule along with Byron and Alcatraz. Unfortunately, we are never allowed to go beyond and visit them, such as the residential area with the living quarters. And that's a shame.

Mysterious Island

I had conflicting thoughts and feelings here and there, but nothing truly serious.

In general, I greatly loved the areas and how they presented extremely different biomes: forest, snow, desert, tropical sea, which offered a more than decent variety on the one hand and avoided what would have been the horrendous repetition of similar landscapes for dozens of hours of gameplay, with the exception of those inside the central pyramidal Megastructure.

The structures, both the scattered ones and those for the puzzles and the Megastructures, create fascinating panoramas where, if you have even a minimal temptation to capture the most beautiful angles, it will be hard to resist. I have absolutely no willpower in this regard and I completely drop my pants in saying so, from the height of the gigabytes of screenshots I've taken.

I adored the endless details, often I believe intentionally excessive and redundant as in the pyramid, as well as their pure design serving nothing. There is, in fact, this sensation of being amidst the work of an army of architects who designed and built for the mere sake of doing so. A kind of open-air museum of architecture.

Only the pyramid offered a somewhat unnatural atmosphere. Perhaps it's because of the way it's built inside, the enormous empty spaces, the feeling of "someone is watching us," "this place doesn't seem truly abandoned," "something is happening behind the scenes here." I still believe this was an intentional aspect, due to the story.

I admit that, and this is part of my conflicting thoughts, I would have perhaps preferred fewer areas but with more puzzles. At the beginning, exploring in search of collateral content is a nice challenge, but the further you go, the more you might end up with the impression of repeating the exact same things, without enough time between doing them once and doing them again in the next area.

I don't know if the feeling was just mine, but finishing a single sub-area (and I mean like West 1-2-3, etc.) in a maximum of 3-4 hours without encountering major difficulties in the puzzles took away some of the enthusiasm to stop for a long time.

But, perhaps, I was the one in a hurry. If I had played at release and not two years later, perhaps I would have felt less of a deficit.

Megastructure - Pyramid

Needless to say, with my extreme love and inclination towards all things Ancient Egypt, the first appearance of the Pyramid during the team's arrival on the VTOL took my breath away. Immense and crammed with enigmatic technologies and promises of mysteries and discoveries, beautiful in its light-colored facades decorated with gold, it was the focal point of the initial part of my playthrough.

I knew we would enter it, but not when it would happen. And my hands were tingling at the thought of what I would see inside.

It was taken for granted that it had to do with the game's progression, and the three laser receivers on the facades were a guarantee of that. What followed, however, seemed like an end-game clause. It was obvious to me that at least three areas corresponding to as many lasers had to be solved for each facade, and then you would get access to the end. Like the Golden Gates later, but much grander.

When we actually set off after the first macro-area, well, I was positively stunned. Especially because this meant at least 3, if not 4 full trips, one for each facade (of which, it was supposed, one final one closing the storyline).

I immensely loved the internal part, just as beautiful and even more so than the external part: the strange and cramped golden corridors, their tight oppression despite the infinite spaces crossed with the VTOL and, like the outside walls, this lingering feeling that there was too much in the construction: too much space, too many decorations, too many seemingly useless elements, too many things that a rational human mind would not only have avoided but would not even have occurred to them.

The soundtrack, then, both for the entrance with the VTOL and for the internal exploration, is the icing on the cake and makes everything more anxiety-inducing.

It made me want to know what it is, how it was built and by whom, why. Consequently, also to move forward with the game, solve another macro-area to be able to go back inside and discover a little more.

And doing it with the others is an addition, especially considering what happens to Byron afterward, which forces the team to stay when they would have wanted to leave.

If I have to be completely honest, I found the puzzles extremely easy.

In TTP, I distinctly remember spending hours on individual puzzles that I found particularly difficult, and not infrequently, I had to leave them aside to do others, only to come back multiple times to try and solve them with a fresh mind.

Admittedly, it's true that my experience in using the devices and understanding the strategies was more limited, and thanks to having finished the first game, it is now easier for me to quickly intuit the correct sequence of actions for a solution.

It might also be a false memory, and I might have spent about the same amount of time, considering that the 120 accumulated hours must include Road to Gehenna, the search for some of the stars, and all the time I always lose taking screenshots (assuming this was counted. In TTP2, the time count seems to exclude things like this).

Yet, despite this, they seemed really quite easy. Easy to the point of starting a new area and finishing all 8 puzzles one after the other, dedicating at most 10-15 minutes to each for the most part, save for a few exceptions (and often due to tiredness), and ending up spending more time getting the two monument stars and looking for all the collateral things on the map.

And those were even marked on the compass.

However, I haven't investigated anything about this and I don't know if it was intentional, to allow more people to enjoy the story without getting stuck for too long, considering that this one is decidedly denser in terms of interactions and dialogues.

The first TTP was an almost exclusively philosophical and exquisitely solitary exploration (not that philosophy is missing in TTP2, quite the contrary, but it is still a very different thing), there were fewer areas and fewer explanations.

Being able to complete an entire macro-area per day and without playing a billion hours straight, in short, felt like a rather fast pace to me.

It must be kept in mind, however, that there is also Road to Elysium, which I have not played yet as I write this.

Perhaps more difficult puzzles were simply separated to make the main game less unnerving and the story followable by more people.

Which, in that case, I honestly approve of.

Furthermore, one should know what their target was: Dark Souls wants to attract people who love near-impossible challenges and extreme gameplay, for example, but it's not certain that Croteam was addressing the same type of people in the puzzle genre.

After all, The Talos Principle is not a pure challenge of puzzles, but a story that continues to unfold from one game to the next, from one DLC to the next, along with its lore.

For the most difficult puzzles, in the end, there are not only the DLCs, as is right, but also the puzzles created by the community.

One thing that slightly frustrated me, though completely negligible and not serious, is the almost total absence of facilitated exits at the end of the puzzle.

In TTP, on the contrary, once a puzzle was completed, there was often a way to exit directly from the zone where the tetromino piece was located, without having to return to the entrance.

Or so I recall, at least.

Honestly, I can't say why they didn't do it this time.

I tried to take a look, and it doesn't seem like it would have caused problems with the puzzle designs. After all, in TTP, it was almost always a simple grate that, once solved, lowered and allowed access to the exit or cut part of the path (I don't remember if there were walls too).

It's clear that, if I remember correctly, it was not present if the puzzle was very simple, and it was often a useful solution for when there were hostile entities that could not be blocked/avoided again or energy walls that could not be opened/jammed again by going back. However, it remains that, especially in some puzzles, it would have been very convenient.

Another thing that I was somewhat disappointed and pleased by at the same time is that each of the 9 main areas is presented with a new mechanic, which theoretically should keep attention high and boredom away,

BUT

the things don't have time to get really complicated.

The first levels, as in TTP, serve to familiarize yourself with the new mechanic and the new device (if there is one), so they are extremely linear. However, the presence of only 8 levels does not allow them to become complex, whereas in TTP there were many more (and fewer areas), and you clearly felt the difference between the first puzzle and the last of an area, as well as between green, yellow, and red puzzles.

I found even those behind the Golden Gates relatively easy.

Furthermore, there is also little summation of the different mechanics, if not rarely and rather vaguely. Only when returning to the central Megastructure are well and truly all those seen in the previous zone, put together somewhat. Yet, where I had imagined extremely complicated puzzles inside the Megastructure, I found everything very smooth—or almost—in the same way.

And here we return to my doubt that they may have left the base game approachable by more players and reserved the major challenges for the DLC and the community.

But I repeat and emphasize: this is not a bad thing, nor is this a criticism.

I have always been and always will be on the side of providing games with different difficulty levels, approachable even by those who are less inclined/expert.

As I said above, if the choice was to leave the main game story-driven, with lighter puzzles to better immerse oneself in the story and putting the others aside, that's perfectly fine.

Okay, I'd say it's time to conclude this long, looong review, by summing things up (but I warned you that you would get a taste of my love for The Talos Principle!).

I consider The Talos Principle 2 the full and worthy successor to The Talos Principle, capable of skillfully picking up its legacy both in graphic continuity, despite being Croteam's first game to undergo the transition from Serious Engine to Unreal 5 (via 4), and in the narrative and philosophical legacy, which hits the mark every time and sparks a potential symposium with every dialogue.

Pandora, Prometheus, the Sphinx, Lifthrasir, Straton, the logs of Trevor and Miranda, as well as all the pages of the past in the terminals, Hypatia's diary about the early days of New Jerusalem, all tickle critical thinking and the desire to go deep, dissect reality, and get to the bottom of the whys, even when the arguments go against our personal point of view, our personal ethics, and morality. There are moments when we are slapped with doses of what appears to us as disillusionment and cynicism, only to then ask ourselves if it's truly so and to question our convictions.

The shift from the solitary digital and fictitious reality of the Simulation to the well-populated real world of New Jerusalem is fluid. The story not only captivates but digs deep into important themes that go beyond the typical philosophy of the franchise, which this time, as we have seen, explores relationships and the birth of a society (or the rebirth of a civilization?).

This time, we also find themes much closer to people and not just existential debates, such as feelings, family, loss and grief, the frustration of those who—in our time—found themselves with incapable governments and limited time that will not stop, because everyone is already dead even if they are still breathing. This shows us, through a marvelous intertwining of characters and personal experiences, how much these "New Humans" are robots more in body than in mind.

We also delve into sophisms like what nature is, what extinction is, what the weight of Homo (Homo mechanicus?) in reality should be, whether it is right to interfere and how much, whether the extinction brought about by humans is natural or an aberration to be fought.

Even the sub-plot that I know exists, which I know I missed for roleplaying reasons (but I will explore it in another playthrough in the future), demonstrates how the city's dynamics have come very close to those of the old world and old humanity, of the wildest Anthropocene.

The very dynamics that later led to the extinction of biological Homo sapiens.

Beyond my regret for having lost a year and a half before actually playing it, I can say I am happy to have believed in the worthy sequel and to have resisted snooping in online discussions to be able to play completely in the dark. No regrets!

Related Articles

If there was something I wanted to discuss more deeply, it's here!

No related article here

(perhaps "not yet"!) : D

In Pills

In Pills

Recap

YASS

- Wonderful graphics, linear legacy of the first chapter

Engaging story, with very human and unexpected twists

Well-written characters, coherent and well-integrated into the setting

Something like almost 170 puzzles to solve, between regular and extra ones

Soundtrack by the same author as the first game, equally wonderful

SO-SO

- Puzzles may be easier than the first chapter

Sometimes you might feel like you're repeating very similar things

For some, the sub-areas may seem endless

Relax-O-Meter

- = to be taken into consideration

- = not a problem but it's annoying to some

- = minor bug/glitch or issue

- = serious bug/glitch or issue